The Nightwatchman

Actors in supporting roles

“The sea was angry that day, my friends. Like an old man trying to send back soup in a deli.” George Costanza

George Costanza sat in the diner with Jerry, Kramer and Elaine and proudly explained how he heroically saved a beached whale in an iconic episode of arguably the greatest show in history, Seinfeld.

On Monday, 2 September 2024, at around 6:30pm, I found myself in a vaguely similar position. Two young women were swept out beyond the rocks between Clifton 3rd and 4th Beach while I was on the sand with Jules and our son Thomas, enjoying what felt like the first day of summer. It was one of those perfect spring evenings where Cape Town tries to fool you into believing that the Atlantic is actually an inviting place to frolic.

Thomas, approaching his second birthday, had been providing the entertainment. His language had exploded over the winter, and he had Jules and me in stitches, pointing at the surfers goading, “Ironing boards! Ironing boards!” Perhaps we should go to the beach a bit more this summer, I suggested to Jules. When I shared this anecdote with my good mate, a surfer who lives a few blocks from Muizenberg’s Surfers Corner, he remarked that his similarly aged daughter would struggle to identify an ironing board at all.

So this is a story I’ve seldom told, mostly because “any ocean rescues to report, boys?” is not the sort of thing that often comes up. Also, I know my mates still won’t let me forget about the time in high school when, during the December holidays, I was caught in a rip current in Kammabaai in Hermanus. In a panic, I put my head down and swam harder than any water-polo coach had ever gotten out of me in training, until a lifeguard appeared barely a metre away from me standing with water up to her sternum asking, “Can’t you stand?”

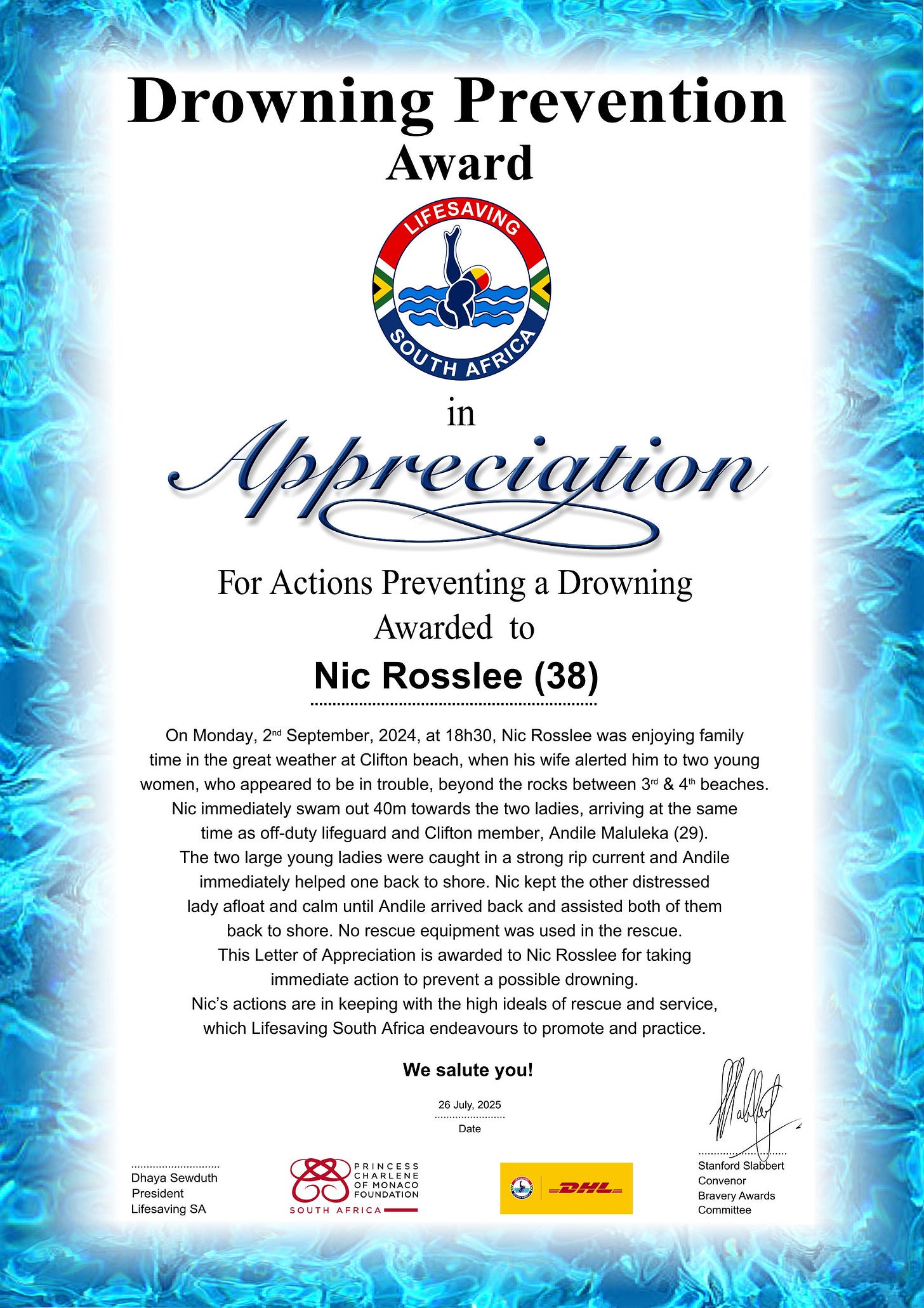

With my credibility as a narrator suitably questioned, I was genuinely surprised when Stanford Slabbert from Lifesaving South Africa got in touch a month ago to say that they’d like to give me a Letter of Appreciation in their annual Bravery and Drowning Prevention Awards for my efforts. I had no idea how many rescues happen on South African beaches every year – I suspected plenty, or that such awards exist.

On that evening in September last year, I only realised what was happening when Jules came running over, flagged down by two women pointing out towards the rocks. The moment my memory takes me back to most is that in the last few strokes before reaching the woman, who was struggling badly, I paused to catch my own breath and thought, “What the hell are you doing? You’ve got a wife and a kid on the beach. Don’t drown.” I came to the conclusion pretty quickly that I wouldn’t be able to swim her back to shore alone, but I thought I might at least help keep her afloat.

Swimming out to her, there were two stories running through my head about friends who’d been in impossible situations at sea, their only hope being that an NSRI rubber duck would appear on the horizon. I hoped that Jules or the other women on the beach were calling the NSRI who have a rescue station at Bakoven just a few kilometres away.

I often wonder what might have happened if Andile Maluleka, an off-duty lifeguard from the Clifton Lifesaving Club, hadn’t been there that day. He’d jumped off the 4th Beach rocks recreationally at about the time I reached Kabelo. He got to the other woman, who was closer to the rocks, helped her to safety, then swam back to guide me and Kabelo to a calmer spot between the rocks of 3rd and 4th Beach. He had no rescue equipment – just an ordinary guy doing extraordinary things.

Perhaps it’s a product of the South African all-boys school environment, where talking about any achievement is akin to putting your head above the parapet – but I suspect many struggle to tell a story where they feel like they did a good job. The truth is, this was not my David Hasselhoff moment. That honour belongs to Andile, who actually knew what he was doing.

On the rocks, I told Kabelo how brave she was for staying calm and she embraced me and wept into my chest. We were now well out of sight to anyone on the beach so I quickly climbed back over the rocks to Jules and Thomas to let them know that we were all okay. The two women who’d first seen the trouble were still on the phone with the NSRI, who were apparently dispatching an emergency vessel of sorts our way.

In South Africa, so much rescue work depends on the non-profit organisations and volunteers giving countless hours of their time to keep our oceans safe. That’s what stayed with me: that the sea can turn on you without warning is something we’ve known from a young age, but knowing there’s this chain of strangers from Lifesaving Club volunteers like Andile to NSRI crews, who show up when they’re needed, again and again.

In cricket, a nightwatchman is a less talented batsman who gets shoved in towards the end of the day’s play so the real specialists can survive until tomorrow. They’re not there to score runs or look graceful. They’re just there to hold on.

I’m not sure if there’s a moral to this story. Perhaps it’s that if you’re ever facing something impossibly big and you are out of your depth, you can do what the nightwatchman does: pad up and try to survive a few overs in the twilight. All the while hoping someone better equipped is already on their way.

But the sea wasn’t angry that day, my friends. Just deceptive. And I was just the nightwatchman. Good enough to hold on for a few overs.

Love this!

So awesome Nic. What a well told story!